Cont.....

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/North-Eastern_Rhodesia

British Central African Protectorate Forces 1889-1901 Part 1

This is my attempt at a Field Force list for the British Central African protectorate (later to become Nyasaland and today known as Malawi) for The Men Who Would be Kings rules. As is usual I’ll start with a wargamers history (part 1) to give the field force some context and then give a selection of units and special rules to help build a (hopefully) historical field force (part 2).

British Central African Protectorate Forces 1889-1901 Part 2

The Sikh soldiers were the mainstay of the early British forces and continued to play an important part right until the end of the era.

African Askari. - It took some time for the local raised Africans to gain the training and experience to become good soldiers but the end of the era they were good enough to be sent to fight in Britain’s wars elsewhere in the world.

Continue reading:

https://jonsotherwargamesblog.wordpress.com/2023/01/08/british-central-african-protectorate-forces-1889-1901-part-2/

The Indian War Memorial: National Memory and Selective Forgetting

By Eric Itzkin

Forgotten men of the Indian Army left their imprint in Observatory, Johannesburg, during the early 1900s. Although their story has been largely forgotten and lost to public memory, a monument at the summit of Observatory Ridge1 honours their memory. This Indian Monument stands as a memorial to Indians who fell in the Anglo-Boer War South African War of 1899-1902, overlooking the valley where Indians served at a remount depot during the War. Erected soon after the end of hostilities, the Indian War Memorial was launched in the first flush of peace amidst a wave of enthusiasm and fanfare. Public interest and understanding of the monument then dissipated over much of the Twentieth Century.

Continue reading : http://samilitaryhistory.org/misc/indianm.html?fbclid=IwY2xjawErTmBleHRuA2FlbQIxMAABHfti9FyYKv5pHZCutBFUxKTUO70duKmp-I6zw6CwW2-GZreGPd5Mm6W0Og_aem_mlq0F-FtotI8ZyevGqWRDg

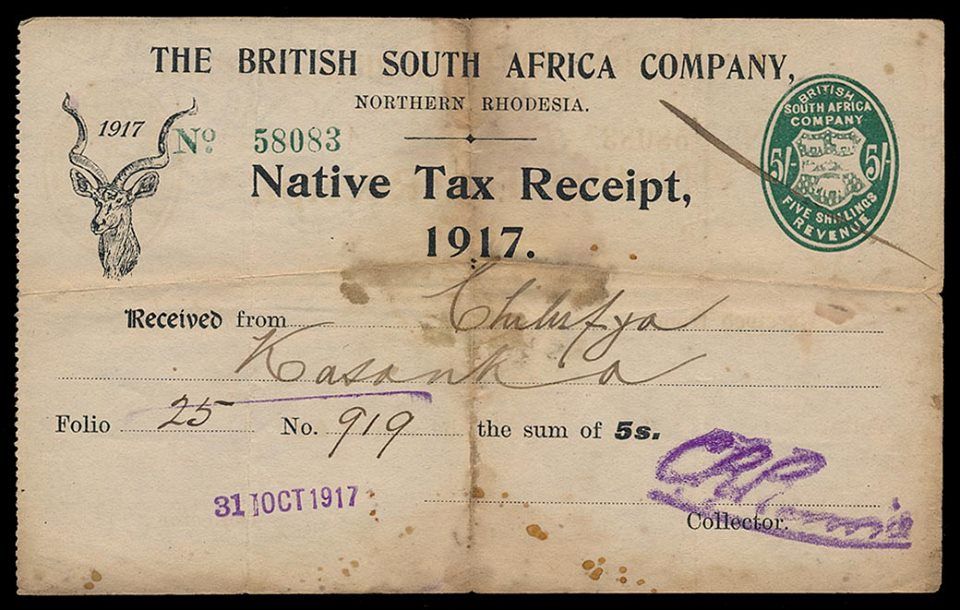

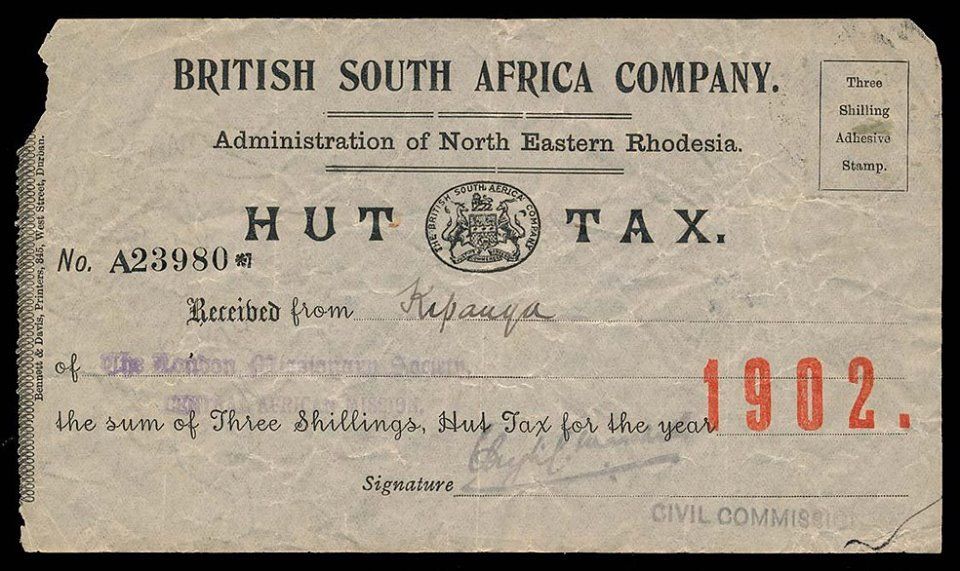

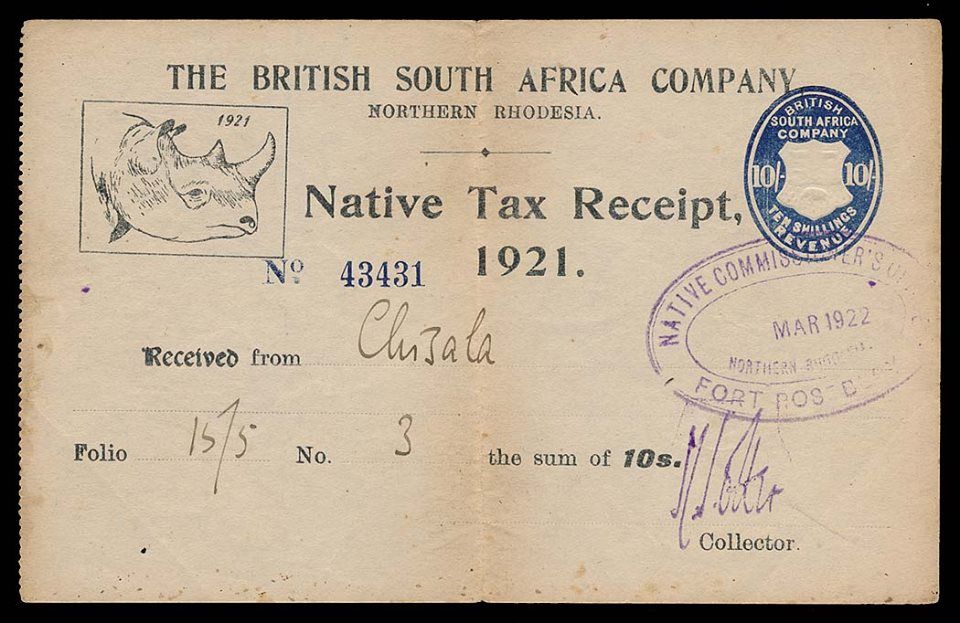

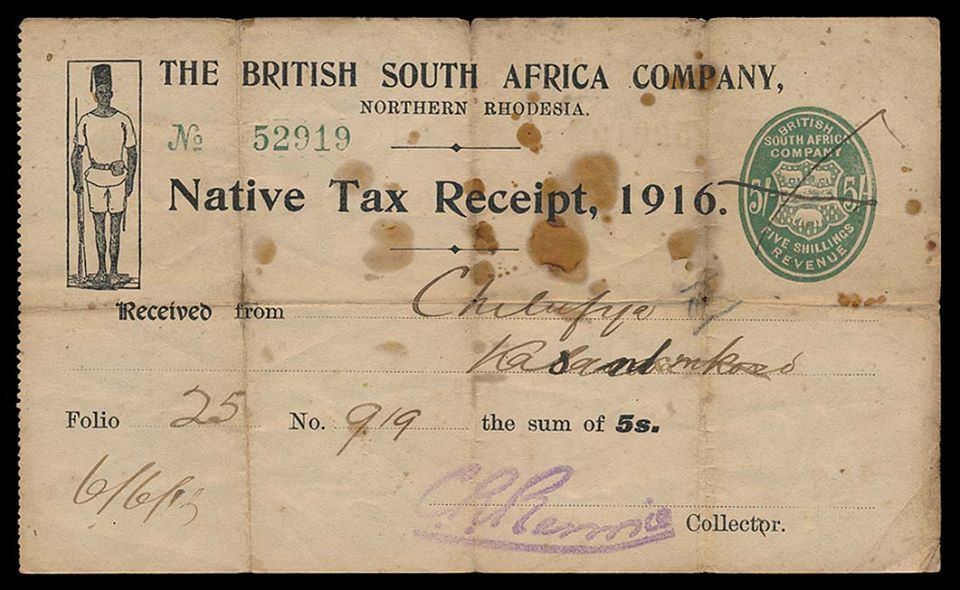

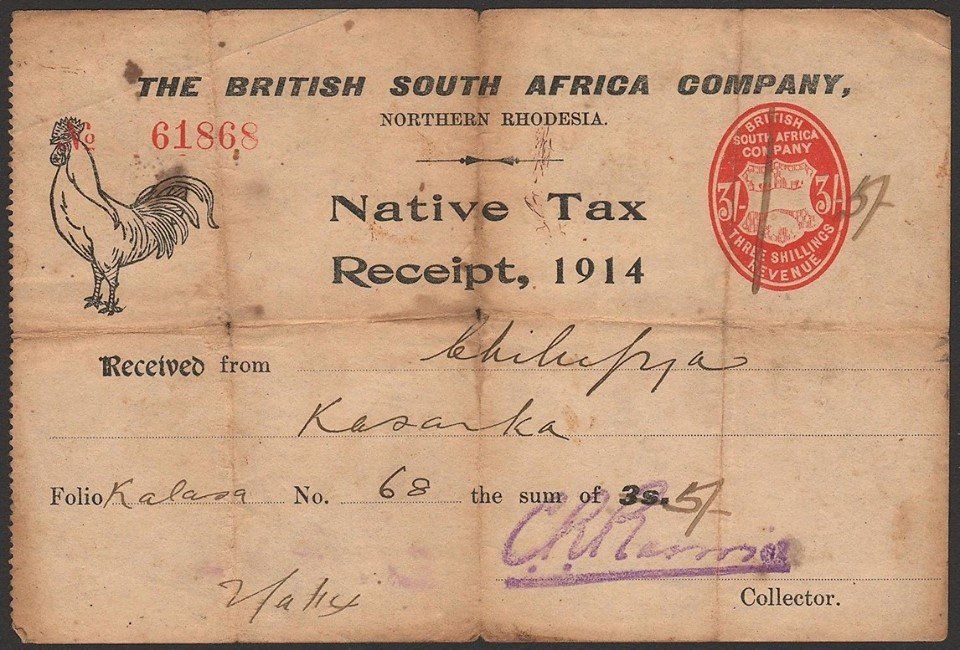

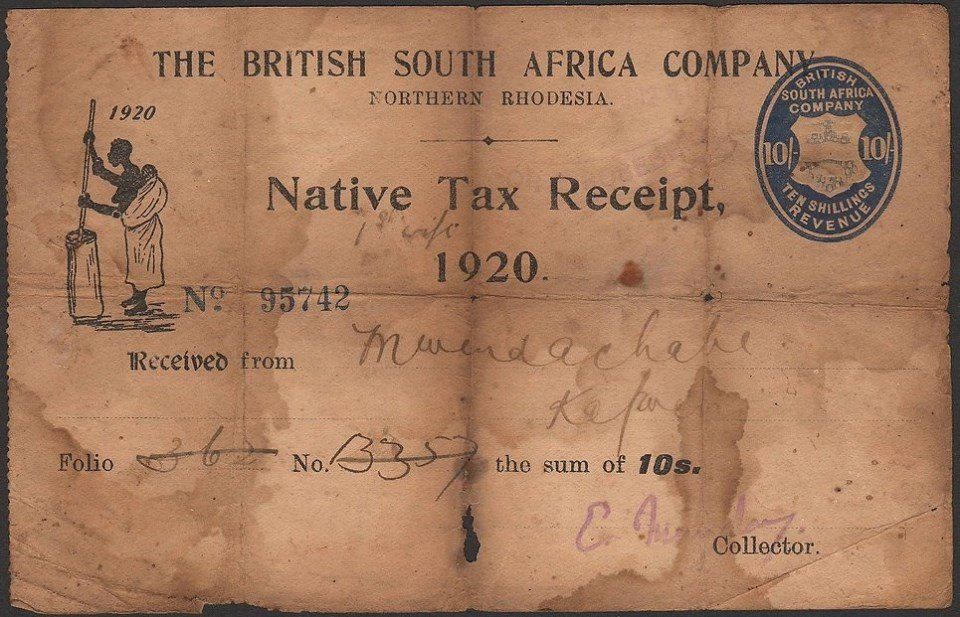

Hut/Native Tax by Colonials

During the Age of Exploration, the Portuguese Empire was the first European power to colonize the East Coast of Africa and gain control of Zanzibar, and kept it for nearly 200 years. Vasco da Gama's visit in 1499 marked the beginning of the European influence.

Berlin conference of 1885 further laid down rules of the game in scramble for Africa for the Europeans to do as they pleased, there was no such a thing as International law for the indigenous, in fact many places in Africa too had their laws under their own Kingdoms, some notable pre-colonial states and societies in Africa, similarily in India, New Zealand, Australia, Americas…etc as such…

Rules of the games were and only for the Europeans and do as they pleased in Africa without any limitations, fear of repercussions or accountability!

The European’s individuals’ policy or practice of acquiring full or partial political control over another Country / Land varied, occupying it as settlers (more like invaders) and fully exploiting it economically to give its own Caucasian people the incentives to manipulate further as it pleased..

Colonials powers never asked any questions but were vanquishing what they saw or wanted, all land assets was carte blanche to them and did as they wished and pleased with it.

Colonialism further practiced of domination, which involves the subjugation of one people to another, further "the state apparatus that was dominant under colonialism created draconian laws for the indigenous or any other people of colour, this was through their own made up land ordinance and legislations for themselves that favoured the Colonials and its people"

When the British arrived and exploited the interior, more changes followed. A British Colonial tax policy was created on the grounds that Britain needed to support its own economy by exploiting and creating foreign markets and sources of raw materials for her industries for their benefit and have full control of it all from raw material to the manufacturing and finances.

In fact, there were resistances toward the Colonialism, Hut Tax War of 1898 transpired, when Protectorate chiefs declared war against the British for imposing taxation on their territories Freetown colony and the Sierra Leone Protectorate and further insight into the Eye of Authority’: ‘Native’ Taxation, Colonial Governance and Resistance in Inter-war Tanganyika by Andrew Burton covers this extensively.

Hut Tax Tokens issued by the British South Africa Company (1903 to 1916) in South Africa and was expanded further north to Northern, Southern Rhodesia, North Eastern Rhodesia…(Zambia, Zimbabwe and Malawi)..

Kenya Native Hut and Poll Tax Ordinances were introduced by the so called settlers upon its indigenous people and bring upon them the thrust in uprooting of their lives, more hardship and strict control through subjugation by a foreign entity was the norm now.

European settlers forcibly moved into the Kenyan highlands in large numbers after the completion of the Uganda railway in 1902. The land they occupied belonged to the Kikuyu, Kamba and other indigenous people.

The European settlers claimed that the land was not being used to its full potential accordingly to them. One would argue, if the locals were self sufficient and it suffices its needs how was this a problem unless one is thinking of exporting and exploiting it.

The Kikuyu, Kamba and others were forcibly moved to ‘Reserves’. Any Kikuyu, Kamba and others who remained on the land were described as squatters. Squatters were expected to work for the new European settlers. The Kikuyu, Kamba and others who were living on their forefathers land were then forced to work in lieu of rent. This tactic by European settlers was used in many African nations including South Africa, Zimbabwe, Zambia, Malawi…etc.

Hut tax was first collected in North-Eastern Rhodesia in 1901 and was slowly extended through North-Western Rhodesia between 1904 and 1913.

It was charged at different rates in different districts but was supposed to be equivalent to two months' wages, to encourage or force local Africans into the system of wage labour. Its introduction generally caused little unrest, and any protests were quickly suppressed.

Zimbabwe 1894-1969: Taxation

- Taxes were introduced by the colonial government to serve two purposes, that is, to force Africans to work for Europeans to earn money to pay taxes and to fund the government

- Whites were not taxed even if their salaries were twelve times more than that of blacks

- The hut tax was pegged at one pound

- The Shona tried to avoid working for Europeans by selling their produce but after the agricultural reforms they were resettled

- Taxes got higher but labour requirements were not met

- Some of the taxes that were paid are poll tax, hut tax, dipping fee, a grazing fee, taxon cattle, dog tax and tax on polygamous tax

Before 1920, it was commonly charged at five shillings a year, but in 1920 the rate of hut tax was sharply increased, and often doubled, to provide more workers for the Southern Rhodesian mines, particularly the coal mines of Wankie.

At this time the Company considered the principal economic benefit of Northern Rhodesia to be as a reservoir for migrant labour which could be called upon for Southern Rhodesia.

The settlers created a Masters and Servants Ordinance which gave European settlers power over their Kikuyu, Kamba and other workers. Africans would be jailed if they did not fulfil the terms of their work contract and even for being disrespectful to the European employers. Chiefs were compelled to supply a set number of workers for European settlers.

In fact the idea of direct African taxation was proposed by British Commissioner, Sir Arthur Hardinge. It was a scheme of tax collection that would be steadily imposed, beginning along the railway centres from Mombasa to Machakos.

The Native Hut Tax was the first to be inflicted in 1901 under the Hut Tax Regulations of that year under the stewardship of Commissioner Sir Charles Eliot.

In this regulation, all huts used as dwellings were expected to pay 1 Rupee annually. The British were commencing a journey to an ultimatum and began by encouraging the locals to work for white settlers and understand the value of money.

With assurance of some superiority, European settlement followed in 1902. The settlement in the colony further became a handsome idea when the Crown Lands Ordinance of that year declared that all land in the protectorate belonged to the British Imperial Government and it would be allocated at will.

However, this move initiated the forceful alienation of indigenous Kenyans from their hereditary land. To further scatter the Africans from their land, the railway station points had higher Hut Tax rates of 2 Rupees, and by 1903, the general Hut Tax had increased to 3 Rupees.

In the years prior to the pandemic, the British saddled African households with a hut tax intended to fund development and war operations. The hut tax was systematically increased as 1918 drew near.

This later was followed by “The Kipande” that was considered a vital tool in running the carrier corps and was introduced through the Native Registration Ordinance of 1916.

The ordinance was ultimately enacted in 1919 and would bring more misery to Africans as if what they were already enduring was not enough and further restricted them to chosen confined areas and constrained their free movements on their very own land.

Union of South Africa

By 1908 the following hut taxes were introduced in the colony of South Africa:

In Natal, under Law 13 of 1857, 14 shillings per hut. Africans that lived in European-style houses with only one wife were exempt from the tax.[2]

In the Transkei, 10 shillings per hut.[3]

In the Cape Colony, various forms of the "house duty" had existed since the 1850s. The tax was legally applicable to all house-owners in the Cape, regardless of race or religion, but was only partially enforced, especially in rural areas. A full and universally applicable house tax was imposed in 1870 (Act 9 of 1870), and was more fully enforced, due to the government's severe financial difficulties at the time.[1870 Note 1]

The highly unpopular tax was terminated in 1872 (Act 11 of 1872), but a new and higher duty was applied by the Sprigg administration during 1878, when government expenditure was extremely high. The Cape's most controversial "hut tax" was established under Act 37 of 1884, and specified 10 shillings per hut with exclusions for the elderly and infirm. It was repealed under Act 4 of 1889.[3]

Mashonaland

In the colony of Mashonaland, now part of modern-day Zimbabwe, a hut tax was introduced at the rate of ten shillings per hut in 1894.[1] Although authorized by the Colonial Office in London, the tax was paid to the British South Africa Company (BSAC), acting on behalf of the British government in the area. Various events such as the introduction of the hut tax, disputes over cattle and a series of natural disasters contributed to the decision of the Shona to rebel against the company in 1896, which became known as the First Chimurenga or Second Matabele War.[1]

The tax was also used in Kenya, Uganda[4] and Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia).[5] In Sierra Leone, it sparked the Hut Tax War of 1898[6] in the Ronietta district, in which substantial damage was sustained to the establishments of the Home Missionary Society. The damage sustained by the Society led to an international tribunal regarding restitution for the damages suffered, brought by the American government on behalf of the Home Missionary Society. The society was compensated for damages done to them by Sierra Leonean rioters.[7]

Liberia also implemented a hut tax, which in one case led to a Kru revolt in 1915.[8][9]

Wiki…

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hut_tax

https://www.globalblackhistory.com/european-occupation-of-land-in-central-kenya-from-1900/

History of tax in Kenya

https://paukwa.or.ke/kecurrency-taxes-taxes-taxes/

The Hut Tax War

https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1057/978-1-349-94854-3_7

Hut Tax Tokens issued by the British South Africa Company

(1903 to 1916)

East Africa..Hansard

Volume 83: debated on Wednesday 23 March 1932 and THE LAW AND PRACTICE OF THE REGISTERED LAND ACT 1902: A COMPARATIVE STUDY

This was a time when the African continent was a white people playground. The Royal Engineers had carved out the extremely fertile Rift Valley into big farms, what was known as “the white highlands” — regions not less than 5000 ft above sea level, which is best suited for Europeans to settle in. But Africans had settled in these highlands, so the colonial government passed The Crown Lands Ordinance of 1902 which permitted land grants to Europeans — meaning that only Europeans could own and manage the highland areas.

The fact ”The 2000 settlers organisations “ who controlled 16000 square miles of PRIME LAND ... The Crown Lands Ordinance of 1902 allowed this clearly… Read into the EAST AFRICA PROTECTORATE (ECONOMIC COMMISSION REPORT) 1919 report on immigration on equal terms

Hut tax was first collected in North-Eastern Rhodesia in 1901 and was slowly extended through North-Western Rhodesia between 1904 and 1913.

It was charged at different rates in different districts but was supposed to be equivalent to two months' wages, to encourage or force local Africans into the system of wage labour. Its introduction generally caused little unrest, and any protests were quickly suppressed.

"This position is summarised in an often quoted extract from a decision of the Kenya High Court in a Kikuyu land case in 1921."

This is the judgment:

"In my view the effect of the Crown Lands Ordinance, 1915, and the Kenya (Annexation) Order in Council, 1920, by which no native rights were reserved and the Kenya Colony Order in Council, 1921, as I have already stated, is, clearly, inter alia, to vest land reserved for the use of the native tribe in the Crown. If that be so, then all native rights in such reserved land, whatever they were under the Gathaka system, disappeared, and the natives in occupation of such Crown land became tenants at will of the Crown of the land actually occupied."

The Ormsby-Gore Commission says:

"This judgment is now widely known to Africans in Kenya, and it has become clear to them that, without their being previously informed or consulted, their rights in their tribal land, whether communal or individual, have 'disappeared' in law and have been superseded by the rights of the Crown.

"It is true that the Kenya Government cannot alienate land from a native reserve without the previous sanction of the Secretary of State for the Colony, but for various reasons we are doubtful whether in the past this has provided adequate security."

Now, my Lords, with regard to the fundamental provision I am going to appeal to Lord Lugard, who had himself originally made the treaties with these native tribes, as to whether there was any understanding or not on their part that they were to be deprived of their land rights by the treaties made, or under the Protectorate afterwards extended when the East African Protectorate was made, because, as I shall show your Lordships later, the fundamental grievance of the natives is that they never surrendered their land rights and regard it as usurpation on the part of the British Government that it should be assumed they had done so. This position was put in a somewhat clearer form by Sir E. Hilton Young in the Chairman's Report on the Central African Territories. He said:

"With regard to land, for example, the areas in which white settlement is to be permitted and what areas should be definitely reserved for permanent occupation by the natives are matters of fundamental importance which should not be decided for one territory without reference to the others. The land question is complicated both in Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland by the presence of large concessions owned

Toggle showing location of Column 1003

by the British South Africa Company and other British corporations, the British South Africa Company holding 2,775,260 acres in North Nyasaland and 2,758,400 acres in the Tanganyika district of Northern Rhodesia, and the North Charterland Exploration Company 6,400,000 acres in the East Luangwa district of Northern Rhodesia."

The Chief says that the trouble is that a number of the actual clans who were land-owning families had their land alienated over their heads, with them on the land, and eventually pressure was brought to bear on them to make them leave it. That is why they have had to go away, far from their own country, as squatters. Chief Koinange says that it is not the Government who are there at the moment who are responsible for this, but it was the Government which was in the country at the time when Mr. Ains-worth and Mr. Hobley were the Commissioners. But the situation remains because no native has any land rights in Kenya.

The land has been granted by the Crown en leases of 999 years to Europeans, free of encumbrances. The Europeans have taken the ground from the Government free of all equitable claims of occupants and free of all encumbrances whatever. If a European buys land and there are these natives upon it, the land is absolutely his land, but there are these native squatters on the land. He may allow them to live upon his land, but he may not treat them as fixed tenants. He may give them as a favour a certain amount of land to cultivate, but he may only do so upon that beneficent principle which General Hertzog is anxious to establish all over South Africa—that the native may only be there as a labour tenant under a legal obligation to labour on it for 180 days a year, subject to legal penal-

Toggle showing location ofColumn 1010

ties of fine or imprisonment if he does not comply with that obligation of 180 days labour a year.

If he is on Crown land he may be able to graze his cattle on payment of so much per head. If he is on the land of a settler, as appears from the evidence, he may in some cases run cattle on that land which is subject to no encumbrances. The settler allows the native who comes back to his old cultivation to run cattle on that land on the condition of the settler himself having all the milk for his dairy. That is why I refer to this statement in the Select Committee's Report that they were satisfied that there was no ground established for any suggestion of forced labour for Europeans in Kenya.

But if you take a man's land and give it away to somebody else, and he has to go away from it, and there is no place for him to go to because he cannot buy land as the Government has made no provision for him buying land, and if you say to him: "You may stay where you are and grow maize and potatoes or run your cattle upon the land on condition that you work for the man to whom the land has been given for 180 days a year at wages of about 4d. a day or, perhaps, 4d. a day and rations," I ask noble Lords on the Government Front Bench, I ask the noble Lord, Lord Cranworth, this question: Do they consider, if you take away a man's land and give him no alternative to living on that land except that he shall work for the new owner for 180 days a year, is that or is it not forced labour?

It is a perfect equivocation when you have taken away people's land and have not provided them with compensation or with anywhere else to go to, and say to them: "You may stay on that land, but it is on condition of your labouring under penal sanction for the present owner of that land," to contend that that is not forced labour. That is one of the things I want further pursued.

I do not think I need elaborate my case further upon that. I have here many quotations showing that great numbers of natives have been evicted from their land in this manner. What I want to ask the Government is, what is the position in Kenya, in Nyasaland and so on, of natives in regard to the land, and what is the principle on which they are going

Toggle showing location ofColumn 1011

to proceed to deal with them? If for the moment we take account of native law and custom, all of these natives would have equitable claims upon that land. It is, no doubt, a very good doctrine to say that the King is the owner of the land. But we know that the land is encumbered with all sorts of equitable tenures upon it of which the British law takes notice.

I have a great admiration of the work done by the noble Lord, Lord Lugard, throughout Africa in regard to what is known as the indirect system of government, because that starts with the view that where you have a community which has sane and intelligent customs and laws, it is the most stupid thing in the world to try to thrust the ram-rod of your British law into those works and appoint a head man to administer it. If you read those most interesting reports on the Kavirondo and Kikuyu land systems you will see that those land systems are very well thought out, very equitable, and very sensible, for the purposes of the tribe which has to live upon the land.

Everybody in Africa has to have land to cultivate. In these over-crowded reserves enormous numbers of land cases arise. In fact, I saw once in a Report of the Kavirondo Association that they were asked how their men were employed and they said that a large part of the time of the men was taken up in deciding land cases. As they have no written records, and no written law, and as this is a matter for those learned in the law and having a good memory, a great deal of palaver is obviously necessary to deal with land cases.

Still it is a good and intelligible system; it is a well established social system which, it seems to me, it would be the greatest mistake in the world to attempt to destroy or overrule. It may be necessary in some cases slightly to modify it in order to introduce the power of making permanent buildings and so on, and those may be matters which will have to be dealt with by the Board that is to be set up under the Native Trust Regulation Law.

The outbreak of the Mau Mau Civil War in 1952 was a factor that shook the colonial government out of its complacency and inertia and brought about the rapid introduction of land registration over the whole of Central Province. The war, fought by Africans against the colonial government and the European settlers, was centered in the Central Province of Kenya where many 188 Ibid, para. 21. 189 Ibid, para. 25(xviii) 190 Ibid. 191 Report of the Nandi District Land Tenure Committee, 1952, para. 25(xx). 91 Kikuyu, frustrated by the government land policy in favour of the European settlers, took to arms.192 The root cause of the war was the deep seated feeling among many Africans that the colonial government had stolen their land. This feeling had developed over many years and several factors were responsible for the outbreak of the war, all stemming from the government's land policy. Page… 121

https://etheses.whiterose.ac.uk/444/1/uk_bl_ethos_303634.pdf

----------------------------------------

I do not think I need elaborate my case further upon that. I have here many quotations showing that great numbers of natives have been evicted from their land in this manner. What I want to ask the Government is, what is the position in Kenya, in Nyasaland and so on, of natives in regard to the land, and what is the principle on which they are going Toggle showing location ofColumn 1011 to proceed to deal with them? If for the moment we take account of native law and custom, all of these natives would have equitable claims upon that land. It is, no doubt, a very good doctrine to say that the King is the owner of the land. But we know that the land is encumbered with all sorts of equitable tenures upon it of which the British law takes notice….column 1014 Speaking from the point of view of the settler, he says that "the large majority of farmers dare not do away with squatters for fear of a dearth of labour." Hitherto the system had been beneficial to the settler, but it was now a menace to the closer settlement project. He emphasises the difficulty of dealing with this large and continually increasing number of detribalised Africans, established in the very centre of European estates, whose numbers, he asserts, are very greatly in excess of the registered number of 133,000. The noble Lord, Lord Olivier, said that there is no longer any room for them in the reserves. In South Africa it is estimated that there are over 1,600,000 of such squatters apart from the urban population, for whom there is no room in the locations. Kenya would seem to be tending towards the same dilemma. This local aspect of the question has been dealt with very fully by the noble Lord, Lord Olivier, and the Colonial Secretary announced in another place the other day that an inquiry is in contemplation regarding it, but I would remind your Lordships that of the nine British Dependencies under the Colonial Office in Africa only two—Kenya and Northern Rhodesia—have adopted the system of native reserves which obtains in the Union of South Africa. Column 1016

THE RISE OF NATIONALISM IN CENTRAL AFRICA

THE MAKING OF MALAWI AND ZAMBIA,’1873-1964

ROBERT I. ROTBERG

"Professor Rotberg has given students of African history a detailed and thoroughly documented study of the creation of Malawi and Zambia and much information on the formation and collapse of the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland. No other scholar has written so full and reliable an account of this recent and complex history. Rotberg had access to hitherto unused official archives and to private correspondence, sources that he supplemented by interviews with many of the European and African participants in the events of the last decades of a century of history. No one can read this story without being impressed by the dizzy speed of change in Africa." —American Historical Review

"No recent study of African nation-making is fuller of fine and finely organized detail.'' -New York Times Book Review

Mr. Rotberg "has seen things which no other historian has seen before —in particular, files relating to all the different kinds of local welfare and other associations of the 1930’s and Forties out of which the nationalist politics of the 1950’s and Sixties emerged. This is exciting stuff, because it shows in convincing detail how far, when the moment for action came, the nationalist leaders were able to build upon an existing network of local associations in which the germ of nationalism was already present. Those who still believe that African nationalism was the work of a handful of unrepresentative agitators should read Rotberg’s book and think again ... Rotberg has written a story of which every Malawian and Zambian will feel proud." —New York Review of Books

"Not only has (Rotberg) written a book that will be of value for years to come—he has written it well! It is the rare historian who so happily combined impressive documentation with a fluent style."

—Africa Today

Robert I, Rotberg, who has done research in both Malawi and Zambia, is Associate Professor of Political Science and History. The Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and a Research Associate at the Center for International Affairs, Harvard University. He is the author of A Political History of and Joseph Thomson and the Exploration of Africa, George Simeon Mwase’s Strike a Blow and Die: A |||

Race Relations in Colonial Africa and Africa and Its Motives, Methods, and Impact (HUP 1970).

THE COMING OF THE EUROPEANS

Yet it must be borne in mind that the negro is a man, with a man's rights; above all, that he was the owner of the country before we came, and deserves, nay, is entitled to, a share in the land, commensurate with his needs and numbers; that in

numbers he will always exceed the white man, while he may some day come to rival him in intelligence; and that finally if we do not use our power to govern him with absolute justice the time will come sooner or later when he will rise against us and expel us ...

—Sir Harry Johnston, British Central Africa (London, 1897), 183-184

THE CHARACTER OF WHITE RULE

We have governed the native and over-governed him. We have taken from him the power of self-determination and have hedged him in with a network of rules and permits, a monotonous, highly regulated and very drab existence. We save him from war and enslavement but we do very little else for him [and] in return for what we have taken away we have given him very little in exchange.

—Mr. Justice Philip Macdonnell, in a letter to the Administrator of Northern Rhodesia, 5 May 1919.

THE BEGINNINGS OF INDIGENOUS PROTEST

We are imposed upon more than any other nationality under the sun. [We] . . . have been loyal since the commencement of this government. . . . But in time of peace the Government failed to help the underdog. In time of peace everything [is] for Europeans only. . . . [We] hope in the mercy of Almighty God, that some day things will turn out well and that Government will recognize our indispensabilify, and that justice will prevail.

—John Chilembwe, The Nyasaland Times, 26 November 1914.

INDUSTRIALIZATION AND THE EXPRESSION OF URBAN DISCONTENT

Whatever you get for us it will be less than the white man gets. Has not a black man blood in his veins too? In any case we don't want to hear about compensation now. We want 5/- a day.

—An African striker to Stewart Gore-Browne, 11 April 1940.

DISCOVERING THEIR VOICE: THE FORMATION OF NATIONAL POLITICAL MOVEMENTS

When is Africa going to be freed? Where is that freedom promised to the world, when is it going to come to be enjoyed by everyone living on this earth?

—Charles Wesley Mlanga, during the first meeting of the Nyasaland African Protectorate Council, 28 January 1946.

PARAMOUNTCY VERSUS PARTNERSHIP THE BATTLE OVER FEDERATION

Some people may think that the African does not see clearly the meaning of Federation. We see its meaning and it means to enslave the African.

—Confidential memorandum of the Northern Rhodesian African Congress, 28 December 1948.

THE FEDERAL DREAM AND AFRICAN REALITY

People who are oppressed come to a stage where ... the people, deprived of expressing themselves by constitutional means ,tend to take means that are violent . . . the Government is forcing the African people into that position. . . . African rule will come. We are going to overthrow you one day; you just wait. ... A minority race can never rule a majority race forever. That has never been done anywhere .

—Wellington Manoah Chirwa, in the Federal Assembly, 16 December 1957, Debates, 1798,2160.

To read more, click the download file

Britain, Northern Rhodesia and the First World War Forgotten Colonial Crisis

Edmund James Yorke Royal Military Academy, Sandhurst, UK

Until very recently the history of the First World War in Africa, if it was told at all, focused on Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck and his selective account of the German campaign in East Africa which he commanded. He described how he had led British forces in a merry dance from Kenya and Uganda to Mozambique and Rhodesia. Africa was there to provide colour to a war which it so conspicuously lacked in Europe. The fates of Africans themselves were scarcely addressed and the use of Africa as a European battleground was rendered as a military strategy rather than a human catastrophe. Edmund Yorke’s Forgotten Colonial Crisis exposes the reality, showing just how narrowly focused, self-serving and misleading are Lettow-Vorbeck’s memoirs, and all the books shaped by them.

The ideas of ‘total war’ may have been developed on the back of the first World War in Europe, but this book shows how relevant many were to the war outside Europe. Fragile rural economies were made to sustain a four-year campaign. Their most important input, labour, was conscripted for the purposes of the war, as porters carried food and munitions hundreds of miles in order to sustain the troops in the field. In Europe stalemate became synonymous with the war’s terrors; in Africa mobility multiplied the demand for manpower and spread the devasta ion. And because the carriers were on the line of march, they were not in their homes and engaged in the more productive business of cultivation. Any economic benefits which had accrued to East Africa and its adjacent territories before 1914 were wiped out by 1919.

In 1916 Northern Rhodesia provided the base for the British invasion of German East Africa (then Tanganyika and today’s Tanzania) from the south-west – just as Kenya did from the north. Under the command of Brigadier General Edward Northey, troops of the King’s African Rifles crossed into southern Tanzania, territory that had been barely touched by German rule. War therefore became the motor of imperialism, opening up hitherto unpenetrated areas of equatorial Africa to the realities of British and German colonisation. But it also undermined empire, as farmers and settlers, as well as police and colonial administrators, were sucked out of Africa’s more developed areas. Northern Rhodesia was one of these. By 1918 the indirect consequences of war confronted it with crisis. At the end of the year Lettow-Vorbeck himself burst into this volatile mix. He finally surrendered on 25 November, two weeks after the German armistice in Europe.

Edmund Yorke weaves together economic, imperial and military history to show the impact of war in ways that each in isolation cannot begin to convey. He provides context and illumination from one to the others. Here in microcosm is a case study of the effects of ‘total’ and protracted warfare. It gives pause for thought – in relation not just to our understanding of the First World War but also to conflict more generally in sub-Saharan Africa.

Hew Strachan Chichele Professor of War Studies, University of Oxford

T A X A T I O N I N T H E T R I B A L A R E A S O F T H E B E C H U A N A L A N D P R O T E C T O R A T E, 1899–1957

*C H R I S T I A N J O H N M A K G A L A University of Botswan

A B S T R A C T : This essay examines, through taxation, the relationship between British colonial administrators, Tswana Dikgosi (chiefs) and their subjects in the Bechuanaland Protectorate from 1899 to 1957. It argues that since Bechuanaland became a British territory through negotiations the Tswana rulers were able to protect their interests aggressively but with little risk of being deposed. Moreover, the Tswana succession system by primogeniture worked to their advantage whenever the British sought to replace them. Taxation was one arena where this was demonstrated. Although consultation between the Dikgosi, their subjects and the British was common, subordinate tribes sometimes fared badly under Tswana rule.

K E Y W O R D S : Botswana, southern Africa, colonial administration, chieftancy, accommodation to colonialism

Download file below to read full paper

The Spectre of a Second Chilembwe: Government, Missions, and Social Control in Wartime Northern Rhodesia, 1914–18

The 1915 Chilembwe Rising in Nyasaland had important political repercussions in the neighbouring colonial territory of Northern Rhodesia, where fears were raised among the Administration about the activities of African school teachers attached to the thirteen mission denominations then operating in the territory. These anxieties were heightened for the understaffed and poorly-financed British South Africa Company administration by the impact of the war-time conscription of Africans and the additional demands made by war-time conditions upon the resources of the Company. Reports of anti-war activities by African teachers

attached to the Dutch Reformed Church in the East Luangwa District convinced both the Northern Rhodesian and the imperial authorities of the imperative need to strictly regulate the activities of its black mission-educated elite. Suspected dissident teachers were arrested, while others were diverted into military service where their activities could be more closely supervised. With the 1918 Native Schools Proclamation, the Administration laid down strict regulations for the appointment and employment of African mission teachers. The proclamation aroused the vehement opposition of the mission societies who, confronted by war-

time European staff shortages, had come to rely heavily upon their African teachers to maintain their educational work. The emergence in late 1918 of the patently anti-colonial Watch Tower movement, which incorporated many African mission employees within its leadership, weakened the opposition of the missions, and served to consolidate the administration's perception of the African teachers as a dangerous subversive force. Strong measures were implemented by the administration soon after the end of the war, with large numbers of Watch Tower adherents being arrested and detained.

ERRATUM: NORTHERN RHODESIA (ZAMBIA) WHITE PAPER ON BRITISH SOUTH AFRICA COMPANY'S CLAIMS TO MINERAL ROYALTIES (Concession agreements; succession of states)

Source: International Legal Materials, Vol. 4, No. 1 (JANUARY 1965)

ERRATUM

The last line of the footnote on page 1133 of the November 1964 issue of International Legal Materials (Volume III, No. 6) was in advertently omitted when the page was printed. The complete footnote is reproduced below.

*(Reproduced from The British South Africa Company1 s Claims to Mineral Royalties in Northern Rhodesia, published by the Govern ment Printer, Lusaka, September 21, 1964. [On October 23, 1964, the British South Africa Company, Northern Rhodesia (Zambia), and the United Kingdom reached an agreement in Lusaka whereby the British South Africa Company agreed to surrender its mineral claims in Northern Rhodesia in return for ?4 million, half to be paid by Zambia and half by the United Kingdom. Northern Rhodesia became independent from the United Kingdom under the name of Zambia on October 24, 1964.)

The Parliamentary Visit to Northern Rhodesia, 1930

Author(s): J. Allen Parkinson, H. Leslie Boyce and P. J. Pybus

Source: Journal of the Royal African Society, Vol. 30, No. 118 (Jan., 1931), pp. 4-26

The object of the Parliamentary Delegation to Northern Rhodesia was similar to the objects of the Delegations of the Empire Parliamentary Association which visited Nigeria in I927-I928, and Tanganyika in I928,'viz., to enable Members representative of the different Parties in the Parliament at Westminsterto obtain direct informationabout the countries for which Parliament has a responsibility, and to report upon the conditions, problems and possibilities of those countries to the Committeeand Membersof the United Kingdom Branch of the Association in both Houses of Parliament.

BCG Vaccination by the Multiple Puncture Method in Northern Rhodesia

By I. L. B R I G G S and C. S M I T H

from tile Federal Ministry of Health, Northern Rhodesia

An investigation into the use of fresh liquid BCG vaccine obtained from the SouthAfrican Institute for Medical Research, Johannesburg, was commenced in October 1953. The opportunity was taken of gaining experience in the use of the Heaf multiple puncture tubercul in test and of comparing the results obtained in BCG vaccinated and unvaccinated subjects with those obtained by the Mantoux intra- dermal method.

The investigation was carried out on pupils, between ages of 5 and 9 years, attending African schools in Lusaka and Broken Hill. Each centre had its own vaccination team.

Commercial Concessions and Politics during the Colonial Period: The Role of the British South Africa Company in Northern Rhodesia 1890-1964

Author(s): Peter Slinn

The British South Africa Company left Zambia unlamented. European politicians from Leopold Moore to Roy Welensky had exploited settler dislike of Chartered as a 'monopolistic' capitalist organization which denied opportunity to the 'small man'. To the African nationalist movement, Chartered's operations represented a blatant example of the economic exploitation of a dependent territory's wealth which was inherent in the colonial system. The manner of the acquisition of Chartered's rights was particularly offensive to African susceptibilities in that those rights were derived from 'treaties' with local chiefs who may or may not have known what they were signing or have had the right to sign away the country's mineral wealth. The company of course saw things rather differently. The Financial Times special feature on Zambian independence carried a full-page advertisement by Chartered claiming credit as the founder of 'Northern Rhodesia now to be Zambia', and pointing out that during the period of Chartered administration the resources of the company were stretched to the limit in order to build the foundations of a modern state and that 'in all the years of development, Chartered played its full part in administration, in prospecting and developing the copperbelt, and in helping forward the economy'. The company's claim to be the founder of the modern state has the obvious justification that it was the Chartered's agents who originally occupied the country on behalf of the British, thereby largely determining Zambia's eventual geographical boundaries. It was also under the Chartered regime that the Zambezi came to be regarded as the boundary of the 'black North', and the slow growth of the white population to 1924 was to prove a decisive factor in the territory's development. Subsequently Chartered played a real part in the rapid development of the copperbelt between 1926 and 1939. It continued to perform quasi-governmental functions in relation to the mining industry, the efficient discharge of which might well have proved beyond the slender resources of the newly-established and understaffed Colonial Office regime. Certainly the size of the mining grants and the freedom from bureaucratic control offered under the Chartered system played a part in attracting the huge investment required from American, British and South African mining interests, though Chartered’s actual responsibility in this matter is difficult to evaluate. However until the Second World War, Chartered’s services, whatever they were, had been cheaply acquired as the company had not been able to extract from the territory a significant sum in royalties.

It is after the Second World War that Chartered’s role in Northern Rhodesia becomes more difficult to justify, particularly in the context of the notions of colonial development then becoming current. Ironically, the greater the wealth Chartered derived from its mineral royalties, the weaker its political position became. Chartered appeared to have outlived any usefulness it may have had to the territory, and to have become a mere parasite feeding off the mineral resources so vital to the country’s development. Even the large sums invested by the company in prospecting in the 1950s66 were seen merely as an attempt to ensure that all possible mining income was extracted by the terminal date (for Chartered) of 1986. To the company, the now enormous royalty income was the proper reward for the shareholders’ long years of patient expectation. Chartered made no real effort to create for itself a continuing role in the country so that even in radically changed political conditions, it might hope to survive as a useful mechanism of development. Lord Robins, true to the Malcolm tradition, was not prepared to ‘squander capital for propaganda purposes’.67 The company faced the prospect of African government with fatalism, following its traditional policy of making no concessions unless absolutely forced to do so. (Thus even in 1949, when the political case for concessions to Welensky w’ould seem to have been overwhelming, Dougal Malcolm only gave way to a virtual ultimatum from the Secretary of State). In the last analysis, the board was probably right in recognizing that no belated public relations exercise would enable Chartered to outlive the colonial regime in Zambia. The final crisis of 1964 was therefore something of a charade, necessarily and skilfully managed by the Zambians to demonstrate the propriety of their slaying of the ‘capitalist dinosaur’.

To read dowload file below..

THE YEAR 1930 IN NORTHERN RHODESIA

W. G. Fairweather

THE year 1930 in Northern Rhodesia has been particularly busy for the Survey Department. This was chiefly due to the mining actIvIty in the northern area and to the rapid development of new townships and the expansion of old, owing to the large influx of traders and business houses. The staff has been augmented; but, although the office accommodation has improved, we still find ourselves somewhat cramped at headquarters, especially when the local field staff returns there during the rains. A general review of the instruments and equipment has been made, resulting in the scrapping of old and obsolete material and its replacement by modern equipment. In this connection it is interesting to note the general adoption of the new Zeiss, Wild and Tavistock theodolites.

Work at headquarters has been unusually heavy owing to the sales of township plots, involving the issue of a record number of deeds and the grant of titles to plots and farms where the terms of occupation have been complied with. There has, further, been an extraordinary demand for printed maps, plans, and sketch-plans in connection with the many and various schemes of development, applications for land, boundaries, and mining activity; and the draughtsmen have been more than fully occupied.

In the field the outdoor staff has been fully engaged throughout the season in special surveys of areas awaiting title and in other unforeseen work, such as the survey of the large timber forests on the Machili River and the levelling and contouring of a suggested site for the new capital of the territory. In one case, where a contoured plan was required urgently, attempts were made to do the work by aneroid. The Paulin type was tried; but the results, although every care was taken, were unsatisfactory, and the work was ultimately done by ordinary levelling.

The outstanding feature of the year has been the completion ,of nearly 70,000 square miles of aerial mapping by oblique photography. This is being done by the Aircraft Operating Company under contract, and when finished will provide the territory with a reliable map to a scale of I/Z 50,000, covering what is at present its most important area under development, namely, the mining area .and the railway belt mostly occupied by European settlers. The 'whole of the photography was carried out without mishap and reflects great credit on the Company concerned. Further contracts cover the production of aerial mosaics, contoured to zo-feet intervals, ,of certain township areas round the principal mining centres, namely, Ndola, Luanshya (Roan Antelope), Nchanga, and Nkana. The mosaics are to be on the scale of 1/5000, and from samples submitted of contour prints it is believed that the finished work will be of a high order of accuracy.

In the drawing office progress has been made with the compilation of the new liz 5°,000 sheets of the country; and four of these based on the aerial survey of the Zambezi River have been completed and are ready for reproduction as soon as time and staff are available for the preparation of the separate colour plates. Constant interruption, however, occasioned by demands for other plans, etc. requiring immediate attention, delays this work, and it will be some time before it will be possible to concentrate staff on this necessary mapping and compilation, work, needless to say, which should be carried out speedily and continuously. More draughts men are obviously required to cope with the many and varied jobs sent to the Department.

For the year 1931 and succeeding years there is an ever-increasing programme of field work of varied character; and it is safe to say that there are years of work to be done, and that a staff double the size can be kept constantly at work both indoors and out in the field and still leave something to be attended to later.

Two new departures have been made this year. One is the attempt to train natives as draughtsmen, and the other to train them as surveyors. The schemes are in their infancy, and the raw material available is probably not much inferior to that in other colonies which have carried out this training in the past; but it remains to be seen whether the methods at present on trial in this colony will produce either a native draughtsman or a native surveyor of real economic value even in a reasonable period of time. Possibly when the local natives have learned the meaning of the terms Ambition, Profession and Work, and have been trained to understand the object of what they are being taught, progress in their education and training in technical subjects such as draughtsmanship and surveying will be productive of concrete results.

The new Survey Rules are now in operation and are giving every satisfaction" In addition full instructions in departmental procedure have been published and distributed for general information to enable each member of the staff to make himself thoroughly familiar with office procedure.

Kenya was one of Britain’s most important colonies. Hundreds of European settlers grabbed and occupied the best agricultural land to grow cash crops such as tea and coffee. Indigenous Africans were brutally evicted from their fertile land and moved into crowded reserves.

Britain's "blood tea" legacy in Kenya

https://www.facebook.com/BBCnewsafrica/videos/300095618833427

Kenya's Talai clan petitions Prince William over land eviction

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-61320475

Great North Road (Credit to GNR)

The British South Africa Company Historical Catalogue & Souvenir of Rhodesia from the Empire Exhibition in Johannesburg, South Africa, 1936-37.

Click below to Download file

Report of the Deputy Administration (Mr. R. Codrington) on the Administration of Northern Rhodesia, 1st April, 1897 to 30th September, 1898

Northern Rhodesian Police, Nkhwazi, Volume 11, Number 3, December, 1963

An interesting extract from the Annual Report of the British South African Company for the year 1897-1898. Some readers will be interested in the names quoted in the report and all of you, no doubt, will be completely mystified as to where these places are to-day.

The following report on Northern Rhodesia covers the period of eighteen months from the 1st of April, 1897, to the 30th September, 1898.

The Administration still continues to be directed from the headquarters at Blantyre in the British Central Africa Protectorate, but it has been decided to remove to a suitable position in the Company’s territory in April next.

The greater portion of the territory has not yet been brought under the direct control of the Administration, but our influence and authority has considerably increased during the period under review.

The revenue for the year ending 31st March, 1898, amounted to £2,065, of which £388 11s. 6d. was derived from licences and stamps, and the remainder from export duties on ivory and the sale of the ground tusks which are paid by native chiefs in recognition of the sovereignty of the Chartered Company. The revenue from the same sources for the half year ending 30th September, 1898, is estimated at £1,200.

The Administrative districts remain as before: Chambezi, Tanganyika, M’weru and Loangwa. A great deal of work has been done throughout every district in construction and maintenance of roads; and in the Chambezi and Tanganyika districts good brick buildings have been erected at every station. In the M’weru district several experiments in planting have been carried out; the palm oil is now thoroughly established and it is hoped that in six or seven years palms will be prominent every where, and an important article of native trade will have been added to the resources of the country, and will help to take the place of the fast decreasing ivory trade, and prevent a revival of slave-dealing, as a means of raising revenue amongst the native chiefs.

A considerable trade in rubber obtained fromthe Landolphia vine has come into existence, and every endeavour is being made by our officials to foster this enterprise, whilst providing, as far as possible, for the protection of the vines. Rhodesian Concessions Company have now with! drawn their agents from Northern Rhod, having apparently failed to discover any mineralised country worth developing. The North Charterland Exploration Company within whose sphere of operations M’peseni’s country lies, are continuing to test the value and resources of their concession

The export of labour to Mashonaland is one of the most obvious directions in which we can contribute to the development and prosperity of Rhodesia, and our preliminary experiments in this direction seem likely to be successful.

The Anglo-German Boundary Commission is at present engaged in the delimitation of the boundary between Lakes Tanganyika and Nyasa, and so far as the result can be foreseen the line will be drawn considerably further south than was anticipated, and will leave some of our stations within a few miles of German territory.

In September, 1897, the Arabs from Senga, which was the Arab headquarters before the overthrow of M’lozi at Karonga, by Sir Harry Benjamin in 1896, attacked Chiwali, a friendly chief, whom Mr. Young, an assistant collector i*1 the Chambezi district, happened to be visiting- Mr. Young was able to keep the Arabs in check five days until reinforcements from the hca quarters of the district at Ikawa arrived, when t Arabs were thoroughly defeated, a large number o them killed, and all the principal leaders captur j, including Kapandasaru, who, since the dcat M’lozi, had been considered their head. cfn events have proved that Arab influence in Nort Rhodesia was almost entirely destroyed, and the authority of our Administration remarkably strengthened. A new station was opened in the Senga country at Mirongo, and Mr. Young was given charge under Mr. McKinnon, the collector of the Chambezi District.

In February, 1898, in consequence of a threaten ed rising of M’peseni’s Angoni, the native troops of the British Central Africa Protectorate occupied M’peseni’s country without opposition. A large number of cattle were captured. Singu, the son of M’pcseni, was tried by court-martial and shot. M’pcscni gave himself up and the pacification of the country was completed.

This country is remarkably well adapted for cattle, and when the herds have had a chance to recover in some measure from the enormous losses suffered at the time of the military occupa tion of the country, they will supply Rhodesia every year with large numbers of cheap cattle.

In June, 1898, Major Colin Harding, C.M.G., arrived at M’peseni’s for the purpose of recruiting natives for police in Mashonaland, and he was subsequently employed in raising and training the native police for service in Northern Rhodesia, which were handed over to the Commandant of the British Central Africa Protectorate Forces on 15th October, 1898.

Stations occupied by Europeans in Northern Rhodesia:

Chambezi District:

Administration Headquarters: Ikawa

Out-stations: Nyala, Mirongo,Ikomba

Church Scotland Mission: M’wenze

Algerian Mission: Makasas

African Lakes Company: Fufe

Tanganyika District:

Administration Headquarters: Abercorn

Out-stations: Sumbu,Mambwe, Katete

London Missionary Society: Niomkolo, Kawimbe, Kambele

African Lakes Company: Kituta

M’weru District:

Administration Headquarters: Kalungwisi (Rhodesian Station)

Out-station: Choma

African Lakes Company: Chienje

Loangwa District:

Administration Headquarters: Fort Jameson (Kapata- moyo)

North Charterland Company... Fort Young (Loangweni) M’sore Chirupe

{With acknowledgements to the British South Africa Company Management Services Limited.)

Tax Revenue Collection in Zambia; a Historical Perspective

1. Early History of Governance and Politics

The earliest known taxation system in precolonial Zambia was the tribute system within chiefdoms and kingdoms. At that time, the territory now known as Zambia, was inhabited by various warring tribes who themselves had fled from the Luba-Lunda kingdom in the Congo and, from the Mfecane in the south. Native chiefs and kings required their subjects and conquered tribes to make regular tributes of livestock, jewellery, grain, salt, animal skins and beer. The chief or king would then, at his discretion, redistribute to meet communal needs such as during traditional ceremonies, during war or famine and to pay members of his staff such as messengers and guards. Strictly however, such a system could not have been said to qualify as a taxation system because it was largely voluntary. Moreover, there was no social contract between the rulers and their subjects. In 1891 King Lewanika of the Lozi, fearing the arrival of yet another conquering tribe from the south following his kingdom’s conquest by the fearsome Makololo, requested British protection. On 17 October 1900, he was informed that the protection of Her Majesty’s Government had been extended to his kingdom and he and his chiefs and representatives of the British South African Company (BSA) signed the Barotse Concession. The concession was confirmed in due course by the British Secretary of State for the Colonies and under its terms, the company acquired trading and mineral rights over the whole of Lewanika’s dominion, in exchange for an annual subsidy of £850, among other advantages.

North Eastern Rhodesia however remained dominated by Arab slave traders. Before 1899 the whole Territory had been vaguely included in the Charter granted to the British South Africa Company. In the same year however, the Barotseland-North Western Rhodesia Order in Council placed the Company’s administration of the western portion of the country on a firm basis. It was closely followed by the North-Eastern Rhodesia Order in Council of 1900 which had a similar affect. The two territories were amalgamated in 1911 becoming Northern Rhodesia, and the the Company continued to administer the territory, subject to the exercise of certain powers of control by the Crown, until 1924. But in that year the British Crown assumed the administration of the territory and terms of a settlement were arrived at between the Crown and the Company. And on 1st April, 1924, Herbert Stanly was appointed first Governor of the territory of Northern Rhodesia with Livingstone as capital.

The Governor was advised by an Executive Council which consisted of five members—the Chief Secretary, the Attorney- General, the Financial Secretary, the Senior Provincial Com- missioner, and the Director of Medical Services, the first cabinet. Provision was also made or the inclusion of extraordinary members on special occasions. The Order in Council also provided that a Legislative Council should be constituted in accordance with the terms of the Northern Rhodesia Order in Council, dated 20 February, 1924, to consist of the Governor as President, the members of the Executive Council ex officio, nominated official members not exceeding four in number, and five elected unofficial members. In 1929 the number of elected unofficial members was increased to seven as a result of the very considerable increase in the European population. During the year 1938 the numbers of official and unofficial members were equalised by an amending Order in Council which made provision for a nominated unofficial member to represent native interests and a reduction by one of the number of official members. This was the first parliament. The seat of government was then transferred from Livingstone to Lusaka in 1935.

2. The First Taxes in Zambia

As early as 1924, the governance structure of Northern Rhodesia was well defined both in terms of the executive and the legislature; cultural and economic transformation had already begun at a rapid pace. Whereas the indigenous peoples of Zambia had long been trading by barter, the coming of the colonial settlers introduced a monetary economy based on the British coinage. In order to coerce the native inhabitants to offer their labour to exploit the resource potential of the territory, the colonial government introduced both a poll tax and a hut tax. The poll tax (personal tax) was payable by every man of working age in both the urban and rural areas. A hut tax (property tax) was also payable by the owner of every hut beginning Since the taxes could only be settled using the settler’s currency, natives had to find work with the settlers so as to earn some money with which to pay their taxes. In this way, the natives were introduced to the monetary economy and wage employment thus setting the stage for a modern taxation system.

3. Early Tax Policy Frictions

Following the discovery of copper and other minerals at present Kabwe (Broken Hill), on the Copperbelt and in the Katanga region of the Congo, there was a rush of European investment to the region. The railway from the Cape was extended in record time from present day Bulawayo to reach Ndola in 1909. By 1940, the major copper mining towns of Luanshya, Rhokana, Mufulira and Nchanga had sprung up as reported by Henderson (1973). Estimates show that up to 32,000 African workers were employed in mining operations in the mines of Northern Rhodesia. Such was the rapid economic transformation that the first recorded industrial action in the history of Northern Rhodesia was ignited by an increase in the native poll tax in 1935. For a racial class already suffering wage discrimination, the tax was oppressive and proved to be the tipping point, which sparked widespread industrial action on the copper mines reports Henderson (1973). Historians now recognise this maiden strike action as the genesis of the Zambian independence struggle.

4. Fiscal Affairs in the Colonial Era

Comparing the revenue basket from nearly a century ago with the present, one finds both striking similarities and stark contrasts. For example, the 1938 revenue report details that Income Taxes, Customs and Excises have always been staples of government revenue. However, there have been additional sources of revenue such as Sales Tax, Value Added Tax and mineral royalties that were introduced at various stages in the nation’s history. ofnote, the native tax was a significant revenue contributor in the colonial era. The Colonial Government faced a large fiscal challenge in maintaining law and order in the vast territory. Infrastructure was rudimentary and malaria presented a constant threat to the settlers. Despite this, the British government was unwilling to send resources to the territory and largely expected the territory to fend for itself. The expenditure outlay of the colony in 1930 shows that district administration absorbed the largest share of expenditure while the police and health expenditures were second and third respectively. Fast forward to 2021, there is uncanny consistency in the pattern of public resource allocation since colonial times.

Corresponding Author: Laban Simbeye, labansimbeye@gmail.com

Citation: Simbeye, L. (2021). Tax Revenue Collection in Zambia; a Historical Perspective. Academia Letters,

Article 2463. https://doi.org/10.20935/AL2463.

[1] Source: Northern Rhodesia Colonial Records

[2] Source: Northern Rhodesia Colonial Records

Sixty Years North of the Limpopo, 1953

James A Henry

Chapter III – Across the Zambesi

The story of the coming of the Standard Bank to Rhodesia & Nyasaland, with some account of its early days there.

While Southern Rhodesia's progress in the nineties was rapid, the same could be said of the other territories in which the Chartered Company had interests – British Central Africa (Now Nyasaland), North Western and North Eastern Rhodesia. The signs of payable gold – the greatest incentive to rapid development – were very much less in evidence in these territories and this, coupled with climatic conditions which were much less healthy than south of the Zambesi, made for far slower progress.

Northern Rhodesia.

The territory now known as Northern Rhodesia was at first administered in two separate portions, North Western and North Eastern Rhodesia, the latter being administered from Blantyre until the Chartered Com pany set up its own Administration in 1895. In North Western Rhodesia nothing was done until 1897 when Robert Coryndon was sent up as Commissioner to Barotseland, with Frank Worthington. But progress was slow and the white population remained very small: as late as 1908 the number of Europeans in Northern Rhodesia was only about 700, of whom 100 were at Livingstone.

The first suggestion that the Bank should open in Northwestern Rhodesia came from Coryndon, the Administrator, in 1903, and the matter was again raised in 1904 by the Chartered Company. At that stage, however, there was no development whatever t at could be looked on as justifying the opening of a an . The railway only reached the Zambesi in June,1904, and it was felt that the real progress of the territory would only become possible when the railway reached the mines at Broken Hill. In addition it was intended to combine the administrations of North Western and North Eastern Rhodesia and there was uncertainty as to where the capital of the territory would ultimately be. The Chartered Company’s administration was at Kalomo, but Livingstone was a larger place, with claims to be the capital, while in 1906 we find a reference to the new capital as probably to be within 20 miles of Broken Hill.

The First Bank in Northern Rhodesia.

In 1906, however, it was decided to open a branch, and Kalomo was chosen, as being the seat of the Administration. There was little else to commend it, for the European population of Kalomo and the surrounding district was only 50, while the place was particularly unhealthy with a death rate of 128 per 1,000.

To open at Kalomo, D. McIntosh was sent up from Bulawayo, and the Branch opened at the end of March, 1906. The Chartered Company had promised to provide accommodation, but found difficulty in doing so. As a temporary measure they managed to supply “a very small room” in the Administration’s store, while McIntosh looked around for other accommodation tionich he finally found in the shape of a converted butchery and baker shop, standing by itself and completely surrounded by tall grass six to seven feet high.

There was little business activity at Kalomo, although copper, lead and zinc mines, 23 in number, were being slowly developed within the Hook of the Kafue, a hundred miles west of Broken Hill. Incidentally, it is interesting to read the names of some of the early mines of Northern Rhodesia—Silver King, Sable Antelope, Chanobie, Blue Jacket, True Blue, Maurice Gifford, Rhodesia Broken Hill, Bwana Mkubwa, and Hippo—and to note how few of these names survive to-day.

Apart from its unhealthiness, the knowledge that a new capital would shortly be set up elsewhere no doubt had much to do with the lack of any progress at Kalomo. A terse description of the place was given by the Bank’s Inspector who visited it in April, 1907: “Kalomo cannot be said to be either a township or a village; there are about 25 buildings dumped down irregularly on the veldt, no drainage has been attempted nor are there any roads: the place, which could be made healthy, is over-run with very tall grass which is responsible for the swarms of fever-producing mos quitos which infest it. There are three local shops”.

To read the full chapter, click on link below:

RHODESIANA Publication 31, September 1974

Edited by W. V. BRELSFORD Assisted by E. E. BURKE

A very interesting publication which covers the early European settlement of the south western districts of Rhodesia and the origins of Postal Communications in Central Africa, The Northern Route.

From Northern Rhodesia to Zambia

Forward

My wife and I lived and worked from 1962 to 1973 in Northern Rhodesia and Zambia i.e. through its period of Independence. Apart from my two three-night stopovers in Lusaka on behalf of Newcastle University, neither of us returned to Zambia until 2012, when we had a delightful month revisiting many parts of the country. We then came across so many Zambians who, hearing that I had once been a District Commissioner at the time of Independence, kept saying "You are a living part of our history, a part we know nothing about! You must tell us what it was like."

Let me start with some answers to a few very basic background questions. Why had I gone to the then Northern Rhodesia in the first place, in 1962? And, in essence, how did the British Colonial Service operate in pre-independent colonies and protectorates?

Cont.............................

https://www.britishempire.co.uk/article/fromnorthernrhodesiatozambia.htm

Rhodesia is the land of limitless horizons, and nothing moves the stranger more than the sheer immensity of the veld. The bush stretches into the distance like a never-ending sea of brown and russet, that changes into green after the rains, and sweeps on against a background of translucent blue. During the brief spells of dawn and sunset the land is plunged into gold and purple, but becomes grim and oppresive under the white glare of the midday sun.

NORTHERN RHODESIA IN WORLD WAR II - A History of Northern Rhodesia L.H.Gann

The protectorate takes the field

When Britain declared war on Nazi Germany in September 1939, Northern Rhodesia found herself even less prepared for battle than did the mother country. Throughout the thirties, the Protectorate, like all British East African terretories, remained responsible for its own defence, and the legislators at Lusaka refused to spend money on askaris. In 1932 the Administration wisely separated the civil and military branches of the Northern Rhodesia Police, the military unit becoming known in 1933 as the Northern Rhodesia Regiment.

cont..

A BRIEF GUIDE TO NORTHERN RHODESIA

Information Department October, 1960 by Tm Wilson

THE ARMS OF NORTHERN RHODESIA

The Arms of Northern Rhodesia are technically described as “Sable six palets wavy Argent on a Chief Azure an Eagle reguardant wings expanded or holding in the taslons a Fish of the second”. The whole device is emblazoned on a Shield which is without supporters or a scroll and motto.

The explanation of the heraldic description is that the general colour of the background on the Shield is black, sable being archaic French and the heraldic term for that colour. On this background are six wavy vertical bars or palets, somewhat similar to the palings of a fence. Their colour is silver or argent, again an old term for that metal. They are usually represented as white when the Shield of the Arms is illuminated in flat colours. These palets represents the Victoria Falls. The upper part of the Shield, or Chief as it is called, is blue, and on this representation of the sky is a fish eagle holding its prey, a fish. The eagle is gold and the fish is silver, its colour being given as “of the second,” that is, the six palets wavy or the second part of the Shield.

The meaning of the Arms is thus a fish eagle with its prey over Victoria Falls, and when it is remembered that Dr. Livingstone's discovery of the Victoria Falls put Central Africa on the map, and that he was the forerunner of our present European settlement and African development, the Arms will be recognised as the most apt design that could have been chosen.

The eagle is common throughout Africa, and is known elsewhere as the sea eagle or river eagle. It completes every river scene in Northern Rhodesia as it perches by the banks or flies high overhead, occasionally uttering its strange wailing note.

The history of the Arms is one of some interest. The question of a design for use on flags, and for possible incorporation in a Public Seal, was first brought up in March, 1925. The first suggestion was that the crested crane should be used, but this was not possible as Uganda was already using that. A symbolic representation of the constellation Orion was then suggested. It was not thought to be practicable, but the argument in its favour was that Orion “was a mighty hunter who drove all the beasts of the field before him,” a prowess which distinguished most early Rhodesians!

In 1926 the Governor, Sir Herbert Stanley, appointed a special committee to consider and suggest designs. At that time the Governor was using his own private seal on documents, and in some instances the seal of the previous British South Africa Company administration was also being used. The continued use of either was decided to be undesirable, and a distinctive design for a public seal for the Government was to be found.

The committee eventually put forward three designs: (a) a river scene with an African in a canoe in silhouette in the foreground, (b) the head of a sable antelope, and (c) a lion looking through a pair of elephant's tusks forming an oval frame. None of these designs was favoured by the whole of the committee, and in 1927 Sir Richard Goode, then Acting Governor, reported the findings and difficulties of the committee. When doing so he put forward a suggestion of his own that the design should be a fish eagle grasping a fish over the Victoria Falls. He pointed out that the faults of the other designs were: (a) a river scene could not be represented properly in heraldry, (b) the sable antelope was used as a supporter in the Arms of Southern Rhodesia, and (c) as the Paramount Chief of Barotseland and Chief of Barotseland and Chielf Imwiko Lewanika used the elephant and buffalo respectively, the use of any lesser animal by the Government would be noticeable in African eyes. It was also mentioned that the use of heraldic lion would be an encroachment upon its use in the Royal Arms.

During its deliberations the committee came to the conclusion that the members did not know enough about heraldry or what was being used by other territories to be able to put forward a sound suggestion,and, odd as it may seem, the Navy was called in to help. A book, Flags of All Nations, was borrowed from H.M.S. Lowestoft at Simonstown.

The method of showing the Victoria Falls in the Arms was the result of a discussion of the point between Sir Richard Goode and the Deputy Master of the Royal Mint who was very fortunately visiting the Falls in 1927. The white parts represented the water, and the black the rocks over which it falls. The Deputy Master of the Mint took a very close interest in the matter and on his return to England he asked an heraldic artist, Mr. G. Kruger Gray, to draw Sir Richard Goode's design. It was sent out in time to be included in his report on the findings of the committee mentioned above. This design was finally accepted by Northern Rhodesia in 1927 and received the approval of the King in 1930, but, in its use as a Shield other than on the Public Seal, it was classed a Badge.

In 1938 the Royal College of Heralds came to the conclusion that the Badge was in fact Arms since the device could not be described as other than heraldic. Accordingly the design was granted to Northern Rhodesia as Armorial Bearings by Royal Warrant dated 16th August, 1939, and formally adopted under section 11 of the Northern Rhodesia Order in Council, 1911.

Roads and Road Transport History Association Limited

1964 OLYMPICS

Zambia became the first country ever to change its name and flag between the opening and closing ceremonies of an Olympic Games. The country entered the 1964 Summer Olympics as Northern Rhodesia, and left in the closing ceremony as Zambia on 24 October, the day independence was formally declared.

Zambia competed in the Summer Olympic Games for the first time at the 1964 Summer Olympics in Tokyo, Japan. 12 competitors, 11 men and 1 woman, took part in 13 events in 5 sports. These were the only Games for Northern Rhodesia. On 24 October 1964 (the same day as the closing ceremony), the country became independent from the UK and changed its name from Northern Rhodesia to Zambia, the first time a country entered an Olympic games as one country and left it as another. For that ceremony, the team celebrated by marching with a new placard with the word "Zambia" on it (as opposed to the "Northern Rhodesia" placard used in the opening ceremony). They were the only team to use a placard for the closing ceremony.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Northern_Rhodesia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Northern_Rhodesia_at_the_1964_Summer_Olympics

Extracts from The Rhodesian Civil War History book:

1978 - The Year of the People; Emergence of ZIPRA; Internal Settlement. Part 7:

The tipping point on whether Zambia would be drawn into a broader conflict with Rhodesia.

‘The scene is more than somber. It’s pretty desperate and needs desperate remedies,’ stated the Rhodesian Central Intelligence Organisation in their mid-year briefing to the Executive Council members, Muzorewa, Chirau, Sithole and Smith. ‘.... our professional assessment is that, individually and collectively, all four of EXCO have lost support...... whereas the Patriotic Front and particularly the Mugabe faction has gained ground and is gaining support ..... you have proved more successful in fighting amongst yourselves than in any way getting to grips with the common enemy.....’ The briefing went on to state, ‘ ....the security situation has never been so desperate.... over 6,000 terrorists within Rhodesia with plus or minus 30,000 lined up against us .... growing to 40,000 before the end of the year....meanwhile our white Security Force diminish in numbers and effectiveness.’ One white Territorial Company strength was being lost each month from emigration.

Lieutenant General Walls comments to the EXCO meeting added gloom to the desperate scene. ‘....unless something positive and effective was done .... within next two or three weeks, then it was the view of the Security Chiefs that some political solution other than that now being pursued would have to be found (to stop the war)....’

Tribal factions had erupted in bickering and disunity within the black EXCO members and in the Transitional Government ranks that ZANU and ZAPU exploited as their members, released from detention, recommenced subversive activities.